Written in the Redwoods: Why I Wrote This Book

(Imperfect Edges)

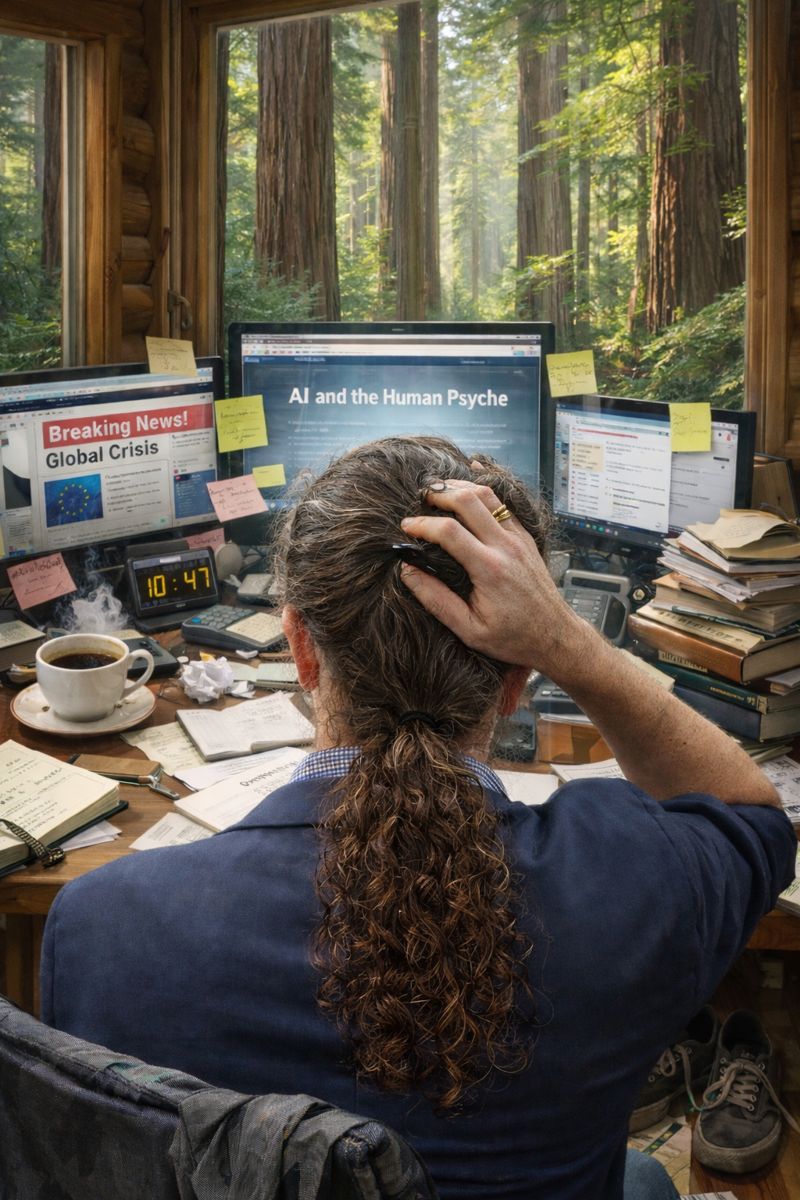

I didn’t sit down one morning with a cup of coffee, stretch my arms like some serene novelist, and decide, “Today I shall write a book about artificial intelligence and the unraveling of the human psyche.” That would have been far too organized. The truth is, this book came out of the same chaotic stew everyone else has been swimming in—stress, confusion, too many browser tabs open, and the creeping sense that the world was speeding up while I was still trying to find my shoes.

Somewhere between seeing patients, raising two small kids, and attempting to build a halfway functional homestead in the redwoods of Humboldt County, I kept running into the same unsettling truth: people weren’t just stressed. They were fraying at the seams. But quietly—almost politely—like they didn’t want to inconvenience anyone with their collapse. And almost every single one of them carried the same private fear, a line I’ve now heard hundreds of times in different forms: “I think it's just me.”

Because I work as a psychiatric and family nurse practitioner, I hear the inner monologues people don’t say out loud to their coworkers or spouses. Over the years I’ve listened to hundreds of people each month describe emotions that don’t fit into neat diagnostic boxes. Anxiety that feels like static in the background. Burnout that looks suspiciously like ADHD until you poke at it. Fear that shows up sideways. There was always stress—this is America, after all—but something shifted in the last few years. The speed of the world outgrew the tools we’d been using to cope with it.

"Somewhere between seeing patients, raising two small kids, and attempting to build a halfway functional homestead in the redwoods of Humboldt County, I kept running into the same unsettling truth: people weren’t just stressed. They were fraying at the seams. But quietly—almost politely—like they didn’t want to inconvenience anyone with their collapse."

My daily routine became oddly symbolic. I’d finish a session with a patient panicking about being replaced by software, close my laptop, and step outside into the quiet of the redwoods. Out there, everything moves at a pace that borders on defiant. The trees are rooted in a way human have forgotten how to be. They’re patient without trying - resilient. They survive lightning strikes and storms and fires and still manage to show up the next season like nothing happened. I wouldn’t say the trees “taught” me anything—they’re trees, not spiritual advisors—but living among them made something very obvious: humans used to be better at adapting. We expected change. We relied on one another. We bent. At some point, collectively, we stopped bending. And then we wondered why we kept breaking.

The more patients I saw, the more it felt like we needed a shared language for what was happening. Not doomscrolling jargon or corporate wellness slogans, but an actual framework for the psychological side effects of living through the fastest technological shift in human history. That’s where the idea for AI-Induced Stress Syndrome (AISS) came from. My clinical attempt to name the thing that was quietly undoing millions of people. You can’t solve a problem until you can describe it.

It wasn’t just stressed-out professionals. It didn’t matter if someone was a surgeon or a substitute teacher or a parent who hadn’t slept well since the early 2010s. Almost everyone described a similar pattern: a kind of anticipatory grief for a future they weren’t sure they’d get to inhabit. A fear of becoming irrelevant in a system that didn’t seem all that invested in keeping them around, and a disorienting sense that the ground they’d built their identity on was quietly moving under their feet.

"If this book does its job, it won’t turn you into a productivity machine or erase your anxiety or make the future feel predictable. But it might give you a little more room to breathe. It might help you think straight when everything feels slippery. It might help you laugh—darkly, if necessary. And maybe it will remind you that being human is still an advantage, even in a world run increasingly by machines."

Somewhere in the middle of all this—writing chapters between clinical notes, wrangling children, checking on the chickens, and occasionally realizing that the “existential dread” I was feeling was warranted—the purpose of the book snapped into focus. I wasn’t trying to warn people about AI or convince them to live off-grid or offer ten tidy steps to a calmer life. Life is rarely tidy, and neither is this moment in history.

I wrote the book because people need tools that actually work in the world we’re living in now. Tools grounded in science, sharpened by clinical experience, and softened by humor because the alternative is crying in the produce aisle. Tools you can use whether you’re sitting in a clinic parking lot trying to breathe, or commuting to a job you’re afraid might not exist in five years, or standing under 200-foot redwoods wondering what comes next for your family.

And I should be honest, I didn’t write this book from any mountaintop of insight. I wrote it from a small office in the woods, usually with a half-drunk cup of coffee and at least one child yelling about an emergency involving a crayon. I wrote it because, like everyone else, I am trying to understand what’s happening to us. I wrote it because resilience has somehow become a buzzword, when in reality it’s a gritty, uncomfortable, deeply human process that requires honesty—not perfection.

If this book does its job, it won’t turn you into a productivity machine or erase your anxiety or make the future feel predictable. But it might give you a little more room to breathe. It might help you think straight when everything feels slippery. It might help you laugh—darkly, if necessary. And maybe it will remind you that being human is still an advantage, even in a world run increasingly by machines.

This book was written for the people trying to stay rooted while the world rearranges itself at high speed. For the ones trying not to lose themselves in all this acceleration. For anyone who has ever felt overwhelmed and needed a clinician to say, plainly and without judgment: you’re not broken. You’re adapting. And you don’t have to do it alone.